Adopting Anti-Racism: Part 2 of 2

by Kyle Massey

In last week’s post, I challenged white readers to acknowledge their privilege, their whiteness, and indeed their racism. I have found when we are challenged for our whiteness, the tendency for most white people is to fall back on our sense of fairness, sensitivity, and democratic inclusiveness. Responses like “How can you call me racist?” are common. This defense question rebukes the assertion of privilege and contends “How can you call me, of all people, racist?” This type of comment is often followed by a recounting of various moral principles that go into great lengths to position most whites as “good people.” Statements like “What more can I do?”, or “Please tell me what I am doing wrong?” are questions frequent in these (often tense) exchanges. When told, a more explicit denial often commences, making extensive use of the word but, saying “Yeah, but do you see how that’s not my intention?” or “Yeah, but do you see the complexity of the situation, here?” The primary goal is self-preservation. Feeling good about oneself takes precedence over the difficult work of identifying and acknowledging whiteness and privilege.

Addressing white guilt or racism?

As I said last week, as a white man I, along with other antiracists born into a white supremacist society, continue to work at acknowledging and unpacking my own privilege. Born into a racist society, we find ourselves thrown into a situation that is not originally of our own making. To address this, some whites try to distance themselves from notions of whiteness and from racism, arguing they would unchoose these if it were possible. Whites often squarely position genocide, slavery, land theft, lynchings, and de jure segregation as part of a past that can no longer be changed. Dismissive notions like “the past cannot be changed and anyway slavery is illegal today” offer reassurance to some whites by discursively transporting themselves to a place of imagined innocence. As a cure to white guilt this is an effective strategy; but it does nothing to challenge racism, the actual problem.

Too often, antiracist activities are focused on alleviating our white guilt which keeps whiteness at the center of antiracism. To pursue social justice, however, we have to decenter whiteness from our efforts and programs for social change. Among other things, this means critically reevaluating our notions of morality: how we understand fairness, how we understand what it means to be a good person, how we understand what it means to be generous or sympathetic or tolerant or a good listener.

Inclusiveness for equity

As antiracists, we need to come together to work for meaningful change, and surely inclusiveness should be one of the central goals. Inclusion would seem to represent an unproblematic, pro-diversity stance, but it is often misused and should be considered carefully. Just as colorblindness shields whites from having to recognize or take responsibility for racist conditions, inclusion is often used to suppress the acknowledgement of conflicting interests. In my experience in schools and on college campuses, I have heard notions of inclusion invoked to criticize people of color for organizing among themselves. Some whites complain that Black fraternities and Black sororities, for example, are overt examples of racism since they seem to contradict efforts for inclusion. Similarly, a Black women’s network that organizes such things as breakfast groups and Bible studies among its members is sometimes criticized by white people for its non-inclusive nature. These criticisms harness a selective narrative of history and ignore the fact African Americans were excluded from joining white Greek organizations for many years. They silence the daily microaggressions experienced by minority populations, minimizing (and sometimes ridiculing) the importance of empowerment within community. Rather than disrupting these important social activities among marginalized members of our population, our efforts for inclusion should be focused on strategies for dismantling structural racism. Working for equity in our society’s institutions and policies, antiracists focus on achieving a fairer distribution of the benefits and burdens of public policy.

Charity vs. Social Justice

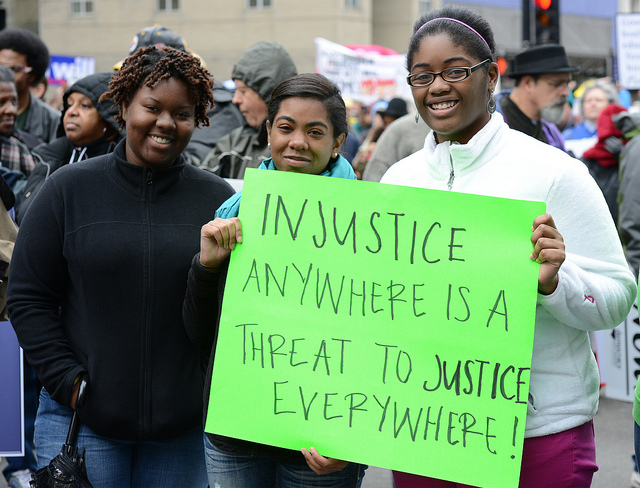

There are numerous causes and issues that need an antiracist framework if we are to realize real and lasting change. Whether our efforts are directed at issues in criminal justice, education, health care, employment, or housing, for example, we must work for social justice. Charitable acts such as donating to food banks or raising money for under-funded schools are essential to reach the immediate needs of disadvantaged in our society; but no amount of charity will ever be enough to bring about real change. Whereas charity is directed at the effects of injustice, its symptoms; efforts for social justice are directed at the root causes of social problems. In other words, social justice addresses the underlying structures or causes of these problems. So, while we should continue to ensure our food banks are well stocked to meet the immediate needs in our communities, we should also critically examine the reasons why so many people in our communities are living in poverty in the first place. And why is it that a disproportionate number of those in poverty are people of color?

Public education is of critical importance to all communities, and as antiracists we should be committed to equity in our education system. We should be asking important questions about current trends in our education system such as: “Why are schools that serve more students of color more often than not the same schools are the most underfunded?” and “Why are schools in low-income neighborhoods that serve a large number of students of color constantly under threat of being closed?” These negative consequences of our current “accountability” culture do indeed effect people of color and their communities much more so than other groups. This is a large part of why I have taken up some of these related issues in public education, advocating for new policies and legislation to help close the opportunity gap in our education system.

We should all get more informed about local efforts underway aimed at social justice, and ask ourselves how we can get involved. Groups to check in with include:

- Texas Kids Can’t Wait

- Texas Hunger Initiative

- Community Race Relations Coalition of Waco

- Act Locally Waco

Kyle Massey is an educator, student, and scholar. Kyle lives and works in Waco, Texas. In addition to his fulltime job as a higher education administrator, in the evenings Kyle teaches undergraduate courses in geography and leadership studies. He is a PhD student at the University of Texas at Austin in the College of Education. Kyle’s research interests include topics related to global citizenship, geography education, and the ways in which various aspects of curriculum and teaching in higher education shape student learning experiences, especially with respect to social and cultural understandings. You can contact Kyle at [email protected], follow him on Twitter @kyledmassey, and check out his website at www.kyledmassey.com

Kyle Massey is an educator, student, and scholar. Kyle lives and works in Waco, Texas. In addition to his fulltime job as a higher education administrator, in the evenings Kyle teaches undergraduate courses in geography and leadership studies. He is a PhD student at the University of Texas at Austin in the College of Education. Kyle’s research interests include topics related to global citizenship, geography education, and the ways in which various aspects of curriculum and teaching in higher education shape student learning experiences, especially with respect to social and cultural understandings. You can contact Kyle at [email protected], follow him on Twitter @kyledmassey, and check out his website at www.kyledmassey.com

The Act Locally Waco blog publishes posts with a connection to these aspirations for Waco. If you are interested in writing for the Act Locally Waco Blog, please email [email protected] for more information.

Photo 3:

- license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/

- Flickr user: Machine Made

Photo 4:

- license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/

- Flckr user: Stephen Melkisethian